Can one worsen an environmental problem simply by promising to solve it?

When confronting environmental challenges, we often think carefully about how policies can alter incentives after they are implemented. But policies can affect behavior well before they are in place--they simply need to be anticipated to occur in the future.

Anticipation can be a powerful force; the promise of some future policy can alter human behavior today. Gun control provides a famous example: calls for tougher legislation in the wake of the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting massacre were followed by a surge in firearm sales.

There are several prominent examples of this in the environmental arena as well. For example, the red-cockaded woodpecker paradoxically saw declines in its habitat after it gained protected status under the U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1973. The mere anticipation of costly land-use restrictions to preserve future settlements of woodpecker colonies provided private landowners with incentives to deforest their properties. Similar behavior has been observed with regard to land development, water withdrawals, and climate policy (here and here). In environmental economics, this phenomenon is broadly known as the “green paradox.”

In a recent PNAS article, Grant McDermott, Chris Costello (emLab Research Director), Gavin McDonald (emLab researcher), and I explore whether this behavior shows up when an announcement is made to close a large area of the ocean to fishing. This kind of policy, known as a marine reserve, has become an increasingly popular tool for marine conservation.

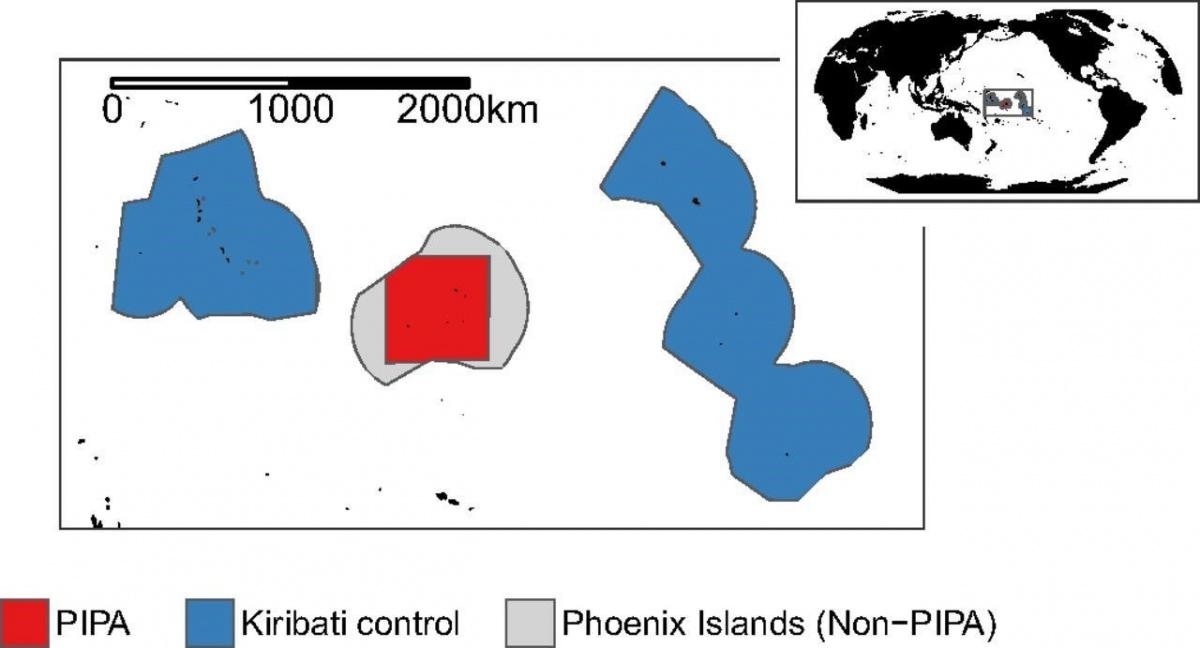

In our paper we closely examine the Phoenix Island Protected Area (PIPA), a swath of the central Pacific Ocean roughly the size of California that surrounds the island nation of Kiribati. As one of the biggest marine reserves implemented to date (see red area in Figure 1 to the left), PIPA has become a poster-child of marine conservation efforts. And for good reason--since its implementation in January, 1 2015, fishing within PIPA has practically ceased to exist.

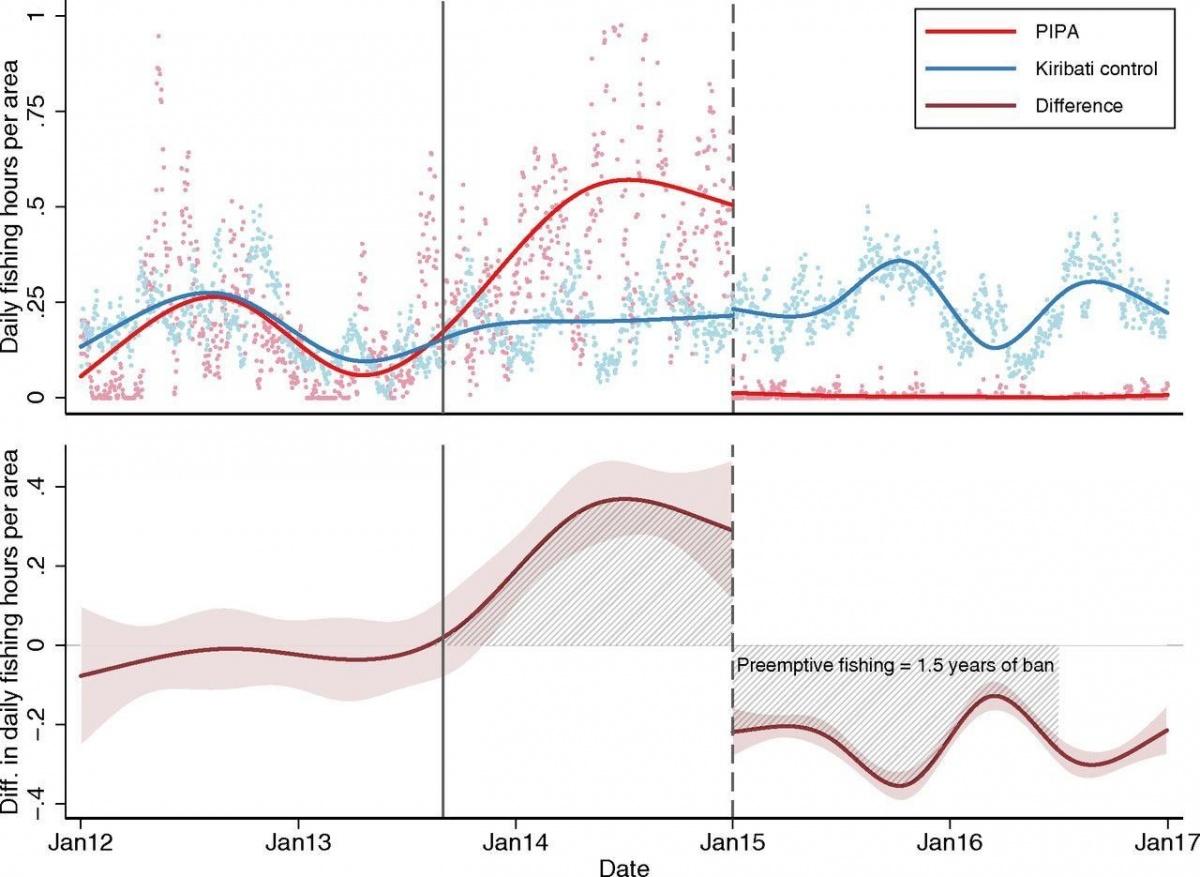

Though this policy ultimately achieved its intended conservation effect, we document a slightly more complicated picture. Using unprecedented satellite-derived data on the universe of all fishing vessel activity from Global Fishing Watch, we examine fishing behavior before PIPA was implemented. Figure 2 below, reproduced from our paper, tells a more complete story of PIPA’s evolution.

In the top panel, the red line shows fishing effort in PIPA. The blue line shows fishing effort over a control region that is similar to PIPA, but where no ban was ever implemented (shown as blue area in Figure 1 above). The dashed vertical line shows the date when the fishing ban was enforced, January 1, 2015. The solid vertical line shows the earliest mention of an eventual PIPA ban that we could find in the news media on September 1, 2013.

Notice that fishing effort in the two regions is almost identical prior to that first news coverage, which is reassuring in terms of the validity of our control region. However, following September 1, 2013, we detect a dramatic increase in PIPA fishing (relative to the control group) until the start of the fishing ban on January 1, 2015. You can see that difference (and the statistical significance of that difference) more clearly in the bottom panel. We calculate that the amount of extra fishing between September 1, 2003 to January 1, 2015 is equivalent to 1.5 years of avoided fishing after the ban.

In a set of extensive robustness checks shown in the paper’s online appendix, we find no evidence that this extra fishing within PIPA was due to other possible factors, such as changing sea-surface temperatures, fishing costs, or fish prices. Thus, we are left with one possible explanation: there was a race to fish in PIPA in anticipation of its future closure. We call this the “blue paradox.” Extrapolating this behavior globally, we estimate that if other marine reserve announcements were to trigger similar preemptive fishing behavior, it could temporarily increase the share of global over-extracted fisheries from 65% to 72%.

Does this mean we should avoid marine reserves altogether? Despite our finding, we believe marine reserves are valuable tools, and our results suggest that PIPA has had an overall positive conservation impact. The fact that the fishing ban remains active, well after the 1.5-year offsetting period, means that conservation benefits are likely continuing to accrue today. Going back to our starting question: yes, one can worsen an environmental problem simply by promising to solve it. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean the solution isn’t worth it.

Our research highlights two important lessons for future marine conservation efforts. First, the sustainability of conservation interventions is paramount to offsetting anticipatory effects. This also suggests that one be patient when evaluating conservation efforts to take anticipatory effects into account. Second, in cases where an over-extracted fishery is near some irreversible threshold, conservation policies should be implemented as quickly as possible after the policy’s announcement to limit the possibility of anticipatory fishing driving a fishery pass its point of no return.

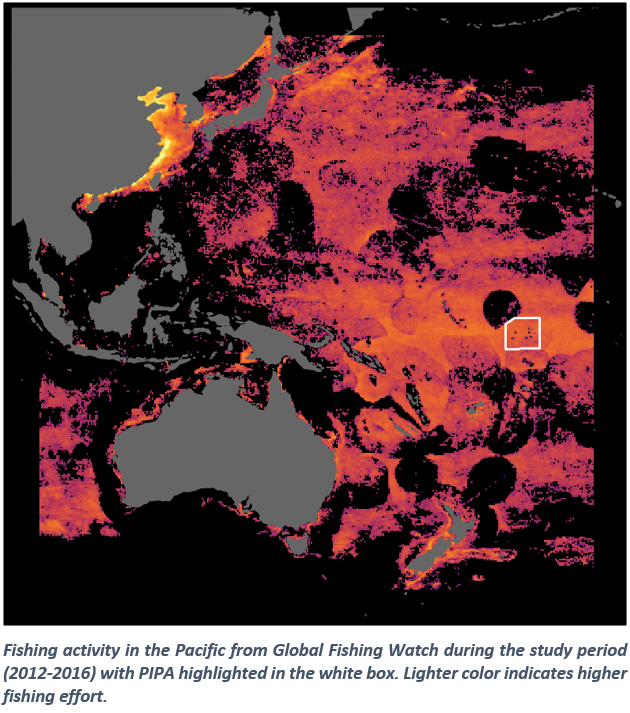

Finally, we think this paper provides an excellent example of how big-data from satellite-based remote sensing can help advance environmental policy making. The figure to the left, which maps all fishing activity from Global Fishing Watch during our sample period, hints at the potential of such a dataset. This paper is just one of many emLab projects in which we’re exploring this and other exciting new data frontiers. Stay tuned.