California is aiming to be carbon neutral by 2045 meaning that it will remove as many carbon emissions from the atmosphere as it emits. While the state has made significant progress in some sectors, especially electricity, its transportation carbon emissions (including the production of transportation fuels) remain stubbornly high, accounting for half of statewide emissions in 2022. To get these emissions under control and reduce the demand for fossil fuels, the state has implemented various policies: Vehicle fuel economy standards are encouraging car manufacturers to make and sell more energy efficient cars; the low carbon fuel standard has been steadily reducing the lifecycle emissions of transportation fuels; and subsidies in addition to the federal ones are making electric vehicles even more affordable for consumers.

While these actions are great for reducing demand for fossil fuels, the state has one big problem. It still pumps out a lot of oil! Until a decade ago, California was amongst the top three oil-producing states in the United States and is now the 7th largest. While California’s oil production has been declining since the 1980’s and now forms only a third of the oil consumed by the state, the rate of decline is not in line with the state’s carbon neutrality goal. Without complementary supply-side policies, California could continue extracting oil and exporting to the global market, potentially undermining greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions.

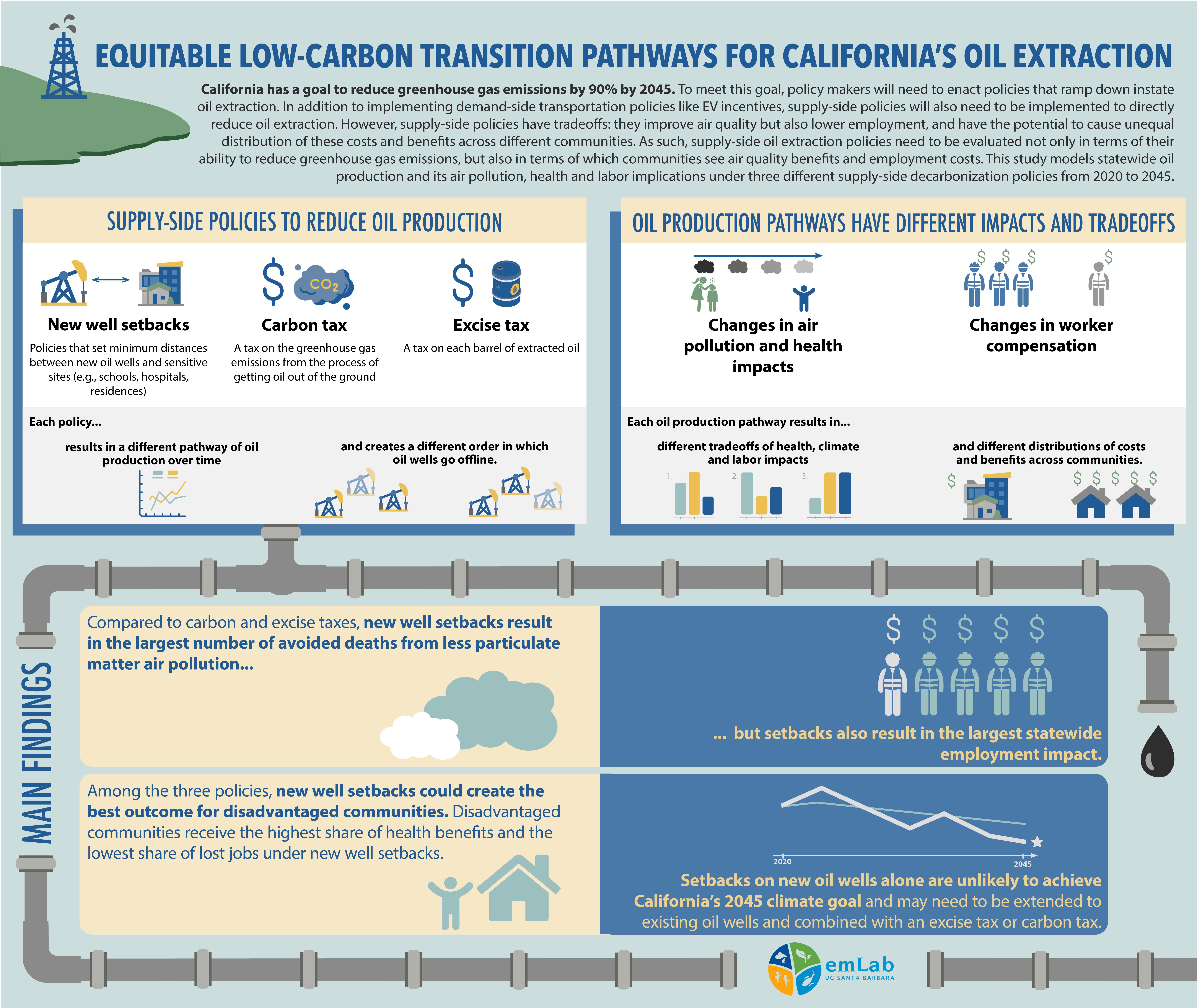

So what supply-side policies could be applied to California’s oil extraction and mitigate GHG emissions? Well, there are three predominant policies: (1) oil well setbacks, which are drilling bans on locations near homes, schools, health clinics and other sensitive sites; (2) oil excise taxes, which are taxes per barrel of oil extracted; and (3) carbon taxes, which are taxes on every tonne of carbon dioxide emitted during oil extraction. While each of these policies can reduce oil production and thus carbon emissions, they also have trade offs for local communities. They could improve air quality but also lower employment near oil extraction facilities, with potential for unequal distribution of these costs and benefits, especially among historically disadvantaged and other communities. To support the state’s goals of achieving a just environmental and energy transition, each decarbonization supply-side policy needs to be evaluated not only in terms of its ability to reduce GHG emissions, but also in terms of which communities see its air quality benefits and employment costs. This policy debate is especially timely: California passed a 3,200 ft setback restriction on new oil wells in 2022 but that law has been suspended until the outcome of a referendum vote in 2024.

Our team of researchers at emLab set out to find the policy that will perform the best in efficiently phasing out oil extraction from California while delivering the best health benefits, the lowest employment impacts, and the most equitable outcomes in favor of disadvantaged communities as identified by CalEnviroScreen. Spoiler Alert! No single policy is the best and all have trade offs. I will lay out the high-level findings here but policy wonks and other interested folks can dig into our article and policy brief published recently in the Nature Energy journal.

Let’s start with what we did. First, we developed a statistically-estimated model of oil field production using over five decades of historical, field-level oil production and reserves data from California’s state government agencies as well as proprietary data on oil production costs. We then imposed different levels of setback policies — 1000 feet, 2500 feet, and one mile — and equivalent excise and carbon taxes to estimate annual and cumulative production and GHG emissions from oil extraction until 2045. Second, deploying an air pollution dispersal model using oil production levels and particulate emissions factors, we estimated the change in air pollution concentration and associated premature mortality in each census tract from each of the policies compared to a no-policy case. Third, using an employment impact model, we estimated the change in oil worker compensation and jobs in each California county. Lastly, we compared the distribution of the health and employment effects of these policies across disadvantaged and other communities.

So what did we find? For a statewide target of 90% GHG reduction by 2045 (which was derived from the California Air Resources Board’s Scoping Plan), we find that setbacks applied to new oil wells generate the largest health benefits in terms of avoided mortality from reduced particulate matter air pollution. But setbacks also result in the largest lost worker compensation. This is followed by excise taxes and carbon taxes. This result is driven by the unique distribution of costs and GHG emissions per barrel of oil associated with each oil field and the population living around and affected by those oil fields. Shorter distance setbacks initially affect oil fields that are upwind of more population-dense locations, whereas excise and carbon taxes have a larger effect on oil fields that have higher costs of extraction and GHG emissions per barrel of oil production, respectively.

To illustrate this result, let’s compare California’s three highest oil-producing counties (in 2019) — Kern, Los Angeles, and Monterey. Production in Los Angeles County has lower average costs per barrel and lower average GHG emissions intensity compared with Kern or Monterey counties but greater health impacts (mortality) and employment intensity per barrel of oil production. Under a setback policy, oil production in denser Los Angeles County is affected more than Kern and Monterey counties, which results in greater health benefits but also higher labor impacts compared with the excise- and carbon-tax policies. Because the average cost of oil production and GHG emissions intensities in oil fields in Kern and Monterey counties are greater than Los Angeles County, both the excise- and carbon-tax policies result in lower health benefits and labor impacts compared to the setback policy.

Next, to understand the equity impacts of supply-side policies, we examined how the statewide health and labor consequences of each decarbonization pathway are distributed spatially across disadvantaged and other communities. We used California’s legal definition of whether a census tract is a disadvantaged community using CalEnviroScreen, a scoring system based on multiple pollution exposure and socio-economic indicators developed by the California Environmental Protection Agency. We found that the disadvantaged communities’ share of health benefits is consistently larger and their share of lost worker compensation is consistently lower under setbacks than under excise and carbon taxes. In other words, setbacks have the most favorable equity outcomes among the three policies. This is an important result for policy making, which can advance California’s goal of achieving a just and equitable energy transition.

Unfortunately, even a one mile setback — the largest considered in our study and much larger than the 3,200 ft currently proposed in California — may fail to meet California’s 90% GHG reduction target by 2045. That means that setbacks on new oil wells alone are unlikely to achieve California’s 2045 90% GHG mitigation target and may need to be extended to existing oil wells and combined with an excise tax or carbon tax. In other words, applying setbacks to new wells is just the first step in decarbonizing California’s oil extraction. Bolder steps will be needed to meet the State’s carbon neutrality goal.