Over the last few decades, many countries have introduced market-based policies to address environmental problems including anthropogenic climate change. Such policies are favored because in theory, they allow an environmental objective to be met at the lowest possible economic cost.

In 2006, California introduced Assembly Bill 32 (AB 32), a landmark climate policy that requires state-wide greenhouse gas (GHG) emissionsto return to 1990 levels by 2020. To achieve this, AB 32 established a GHG cap-and-trade program which started in 2013. It is now the world’s second largest carbon market.

From the very beginning, this program has been the focus of environmental justice (EJ) scrutiny. In particular, advocacy groups are concerned that cap-and-trade may be widening the already large difference in local air pollution exposure between disadvantaged and other communities. EJ concerns led to a temporary pause in the program’s development in 2011 and nearly halted renewal efforts in 2017.

Why might an environmental market alter the gap in pollution exposure? A market-based policy induces relatively less pollution abatement from high marginal abatement cost polluters. If disadvantaged communities, which are typically exposed to higher pre-policy levels of pollution, are downwind of these polluters, a market-based policy will widen the EJ gap. But if other communities are downwind of these polluters, the EJ gap will narrow. For a policy regulating global pollutants like GHGs, the EJ gap effect depends on the coproduction of GHGs and local pollution emissions.

Figure 1. This figure shows our approach to model pollution exposure. The points are the facilities regulated by C&T in California. Each line represents an air parcel trajectory using the HYSPLIT model for January 2017.

In short, it is ambiguous whether the EJ gap would widen or narrow following the introduction of an environmental market, emphasizing the need for causal evidence in the case of California’s carbon market. In a new working paper titled “Do Environmental Markets Cause Environmental Injustice? Evidence from California's Carbon Market”, we show that rather than increasing the EJ gap, California’s carbon market reduced the difference in local air pollution exposure between disadvantaged and other communities across California since its 2013 introduction. However, it is important to note that the program has not come close to entirely eliminating the EJ gap. Answering this question can be challenging for two main reasons. First, one needs to establish how the carbon market causes a change in pollution emissions. Second, one needs to determine where this pollution ends up across the state. To do this, we embed a pollution dispersal model within a causal inference statistical framework. This computationally-intensive modeling involves roughly 11 million pollution particle trajectories from over300 emitting facilities between 2008-2017 (as illustrated in Figure 1).

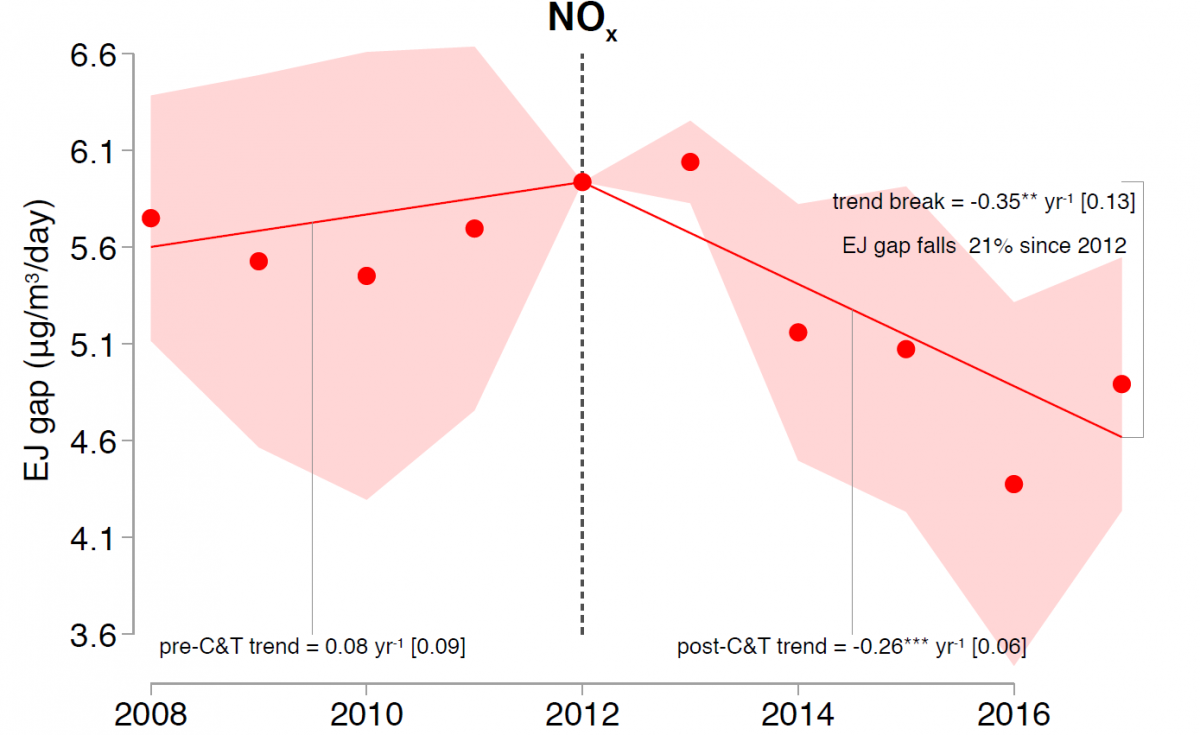

Figure 2 shows our main result for NO exposure (in the paper we show very similar results for SOx, PM2.5, and PM10. We highlight three main findings.

First, consistent with previous work and existing EJ concerns, we document that baseline pollution exposure prior to the program’s introduction was unequal: environmentally-disadvantaged communities - as legally defined by California legislation - are on average more exposed to pollution coming from facilities regulated by the cap-and-trade program. Furthermore, this EJ gap increases between 2008 and 2013. That is, the EJ gap was an increasing problem in the years leading up to the program.

Figure 2. This graph shows the time evolution of the EJ gap throughout the 2008-2017 period. The EJ gap is defined as the average difference in exposure between disadvantaged communities and other communities.

Second, since the start of the program in 2013, the EJ gap has fallen. Specifically, we estimate that the EJ gap was reduced by 21-30% across exposure for NOx, SOx, PM2.5, and PM10 since the start of the program. Third, just because the EJ gap has fallen, it doesn’t mean that the C&T program has completely eliminated it. Indeed, by 2017, the EJ gap was more or less where it was in 2008. Environmental inequities indeed remain.

California’s GHG cap-and-trade program has lowered the local air pollution exposure gap between disadvantaged and other communities across the state. However, our results do not suggest that market-based environmental policies will always reduce disparities in pollution exposure, nor do they imply that California’s climate policy has reduced inequality along other important dimensions, such as the costs of complying with the policy and political access around policy decisions.

Our result also does not imply that cap-and-trade or other market-based policies in general are the right policies for dealing with EJ issues. Market-based environmental policies are designed for economic efficiency: in theory, they deliver an overall environmental target at the least possible compliance cost. But the environmental market forces they unleash, like all market forces, are agnostic about distributional consequences. For California, it happens that the EJ gap was reduced. But in another setting (or even California in the future), the EJ gap could rise under cap-and-trade. As such, while we document the cap-and-trade program reduced California’s EJ gap during its first five years, it would be wrong to argue that it is the right policy to address EJ concerns moving forward. EJ problems need EJ-specific policies.

This is just the beginning: further research is needed to characterize the conditions under which environmental markets can broadly worsen or improve environmental inequality.