Does a green transition mean less jobs?

I am fresh off the plane from a weeklong trip to Paris where my ancestors (I am from Quebec, Canada) are angry. The 'yellow vest movement' has taken France by storm, and I was fortunate to arrive at the airport before the protests of December 1st turned to rioting and violence.

One motivation for the yellow vest demonstrations is France's "green tax," an increase in the sales tax on gasoline and diesel fuel. The tax was implemented in 2018, and further increases have recently been proposed for 2019. This has literally fueled the anger of many, including a few of the Uber drivers who offered me transportation and their interpretation of the current events while travelling through Paris and the surrounding cities.

[Update: on December 4, the Macron government announced it is suspending the gasoline and diesel fuel tax increase for 6 months]

"Diesel cars are the least polluting," claimed one of my drivers, and another asserted that the new tax was just a "money-grab" by the government that has nothing to do with curbing carbon emissions. When my drivers asked what I did for a living and why I was in Paris, I hesitated to say that I'm an environmental economist, and that I was in the City of Lights for a conference on the green transition.

But I am, and I was. It was a privilege to give a keynote "scene-setting" presentation at the OECD's 2018 Green Growth and Sustainable Development Forum.

This year's theme was "Inclusive solutions for the green transition: Competitiveness, jobs, skills, and social dimensions." With this in mind, I recently began a new research project to determine how the renewable transition in the electricity sector will affect labor markets.

Renewables, which I define as wind and solar electricity, now make up about 10% of the total electricity generation capacity in the U.S., and represent the fastest growing component of the sector. This rapid growth is the result of many different factors, including the Renewable Portfolio Standards requirements, now in place in 29 states, and the falling cost of installed renewable capacity. Some states have emerged as strong leaders in renewable development, particularly my home state of California, where Governor Brown recently signed Senate Bill No.100 to achieve 100% carbon-free electricity by 2045.

One key question that we have little empirical evidence to help us answer is: How will the low-carbon transition affect labor markets? To address this important question, I compared the growth rate of state-level labor market outcomes (employment rate, total hours worked, average weekly wage rate, and total wage bill) between 2000 and 2016, for what I defined as "green" and "gray" electricity states. Green states are those where non-hydro renewables grew by more than 10 percentage points between 2000 and 2016. Eighteen states (found mostly in the western United States) qualify as green, and the remaining gray states account for the rest of the country.

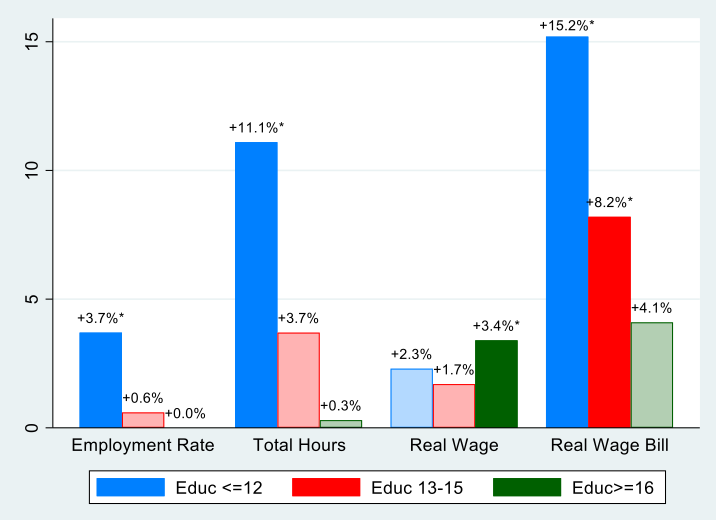

Using a difference-in-difference estimator and data from the U.S. Census and the American Community Surveys, I found that labor markets fared better in green electricity states, especially for lower education workers. The bar graph below shows estimates of the difference in the growth rates of labor market outcomes between green states relative to gray states, by worker education level.

These results indicate that labor market conditions have improved more in green states since 2000, and that the primary beneficiaries of this transition are lower education workers. For example, the total labor compensation (wage bill) accrued by workers with a high school degree or less grew 15% more in green states relative to gray states. This difference is not negligible. Other estimates suggest that green states created 15,000 more jobs per year (out of a base of 50 million workers) than gray states.

Much work remains to be done in establishing these results and determining whether they are the "definitive" labor market effects of the low-carbon transition. For one thing, difference-in-difference estimators are sensitive to assumptions about underlying trends. Furthermore, not all of these estimates are statistically significant (for the interested readers, the starting point estimates in the bar graph are statistically significant at the 5% level), and there may be spillover effects between states that I have not yet accounted for. I am still working to better understand the economic channels through which renewable energy expansion affects labor demand and supply, and in the coming weeks I will collaborate with the emLab team to address these issues and extend the analysis.

So going back to my initial question-- Does a green transition mean less jobs? The preliminary evidence I've produced in my research suggests that the renewable energy transition may improve labor market opportunities, or at the very least, may not lead to the large reductions in labor market activity that some have forecasted.

We can hope that the suspension of the fuel tax increase in France will bring an end to the yellow vest protests, but at this point, those protests represent much more than just a frustration over green taxes. Nevertheless, the situation in France demonstrates that the transition to a low-carbon economy must be paved with policies that ensure buy-in from everyone, and offer inclusive solutions for the regions and people who may have to pay a disproportionate share of the transition's cost.