Our team recently published a paper in Conservation Science and Practice that we’re excited to share with you. Before we dive in, let’s go over a little background information.

What are Marine Protected Areas and why are they important?

Marine Protected Areas, or MPAs, are a globally recognized tool that benefits ocean ecosystems, fisheries catch, and marine populations. MPAs are designated areas where extractive human activities, like fishing, mining, and dredging, are limited in order to provide refuge for the recovery of vulnerable species and ocean ecosystems. Fully protected MPAs completely prohibit all extractive activities but allow for recreational activities like swimming, diving, and boating. MPAs are widely used across the globe to meet conservation objectives, like increasing the biodiversity (the number of different species) and biomass (the total amount of animals) within their boundaries. They can also increase the number of fish outside the protected area which can then be caught, thereby increasing catches in the areas surrounding an MPA. Using MPAs as conservation tools has become so popular, in fact, that the Global Ocean Alliance has called for 30% protection of the world’s oceans by 2030 (coined “30x30”).

Around 190 countries have agreed to participate in “30x30” and many other countries have made their own commitments to ocean protection. For example, in 2019 Bermuda committed to create a Marine Spatial Plan, including a road map of sustainable development of ocean industries and protection of at least 20% of the country's waters in Marine Protected Areas. After gathering scientific data and collecting stakeholder and ocean user input, Bermuda released a draft Marine Spatial Plan for public review that included a proposed network of MPAs designed to benefit everyone in Bermuda.

With calls to increase ocean protection at both global and local scales, literature containing recommendations for designing MPAs (things like the shape, size, and location of MPAs) has skyrocketed. For practitioners and decision-makers who are tasked with developing MPAs, this means a lot of reading and additional research to figure out where to start. We wanted to make this process a little bit easier for them and create a one-stop shop for MPA design. We searched the literature, pulled out key MPA design recommendations, and made them more digestible. We also added information on data, models, and tools that could help kick start the MPA design process.

This sounds like a huge undertaking - why tackle a project like this?

Through our collaboration with the Waitt Institute, we’ve worked to provide technical advice to support several countries, such as Bermuda, Maldives, and the Federated States of Micronesia, who are developing their own Marine Spatial Plans, which include MPAs networks to conserve their waters. As part of our efforts, we collaborate with government officials and spokespeople for the local communities to best understand their specific economic and conservation goals so that we can support each country’s efforts to design MPAs that meet their specific goals for their ocean space.

During these meetings, we used MPA design recommendations from many reports and papers, but we realized we didn’t have a single source that brought all these recommendations together for us. These recommendations are vital to the planning process as they help us decide things like: What shape should the MPA be? What size? Would placing it in this area be better than the area 100 meters away? How can an MPA work best for fishers? Contradictions within literature certainly didn’t help to answer these questions; an MPA plan that worked in one area may not guarantee success for our country partners. We wanted to make this process easier for everyone, and make more digestible MPA design guidelines that included the details necessary for our country partners (and ourselves) to make informed decisions on which guidelines to focus on for their specific MPA plan.

We mentioned Bermuda’s draft Marine Spatial Plan earlier in this blog, and we’re proud to have been able to provide support to the Government of Bermuda in this work. While our condensed guidelines weren’t available for that project, we often found ourselves wishing that something like this had existed. Now that our research on MPA design guidelines is complete, we’re excited to be able to bring this tool to other country partners that are thinking about their own marine spatial plans.

Okay, enough background - what did we actually do?

We started by taking a deep dive into the literature, searching through peer-reviewed journal articles, reports, and other documents that might include recommendations for MPA design. We used a web search to start and found 112 documents to review. As we worked through these documents, we continued to add to our list. Many of the added documents were referenced within the papers from the original search and others were ones we knew about from previous projects. We didn’t mean for this to become a fully exhaustive literature search (finding all the papers ever written about the topic), but we wanted to make sure that we had a good understanding of the most commonly reported MPA design recommendations. We ended up with a total of 219 documents from 2000-2020 to review. No one heard from us for a while after that, since we were trapped in a cave of papers to read! We reviewed each document for recommendations on the physical attributes (things like the shape, size, and location of MPAs) and started building our comprehensive list. When we finally emerged from our cave, we had a list of 307 recommendations (56 documents) for MPA design.

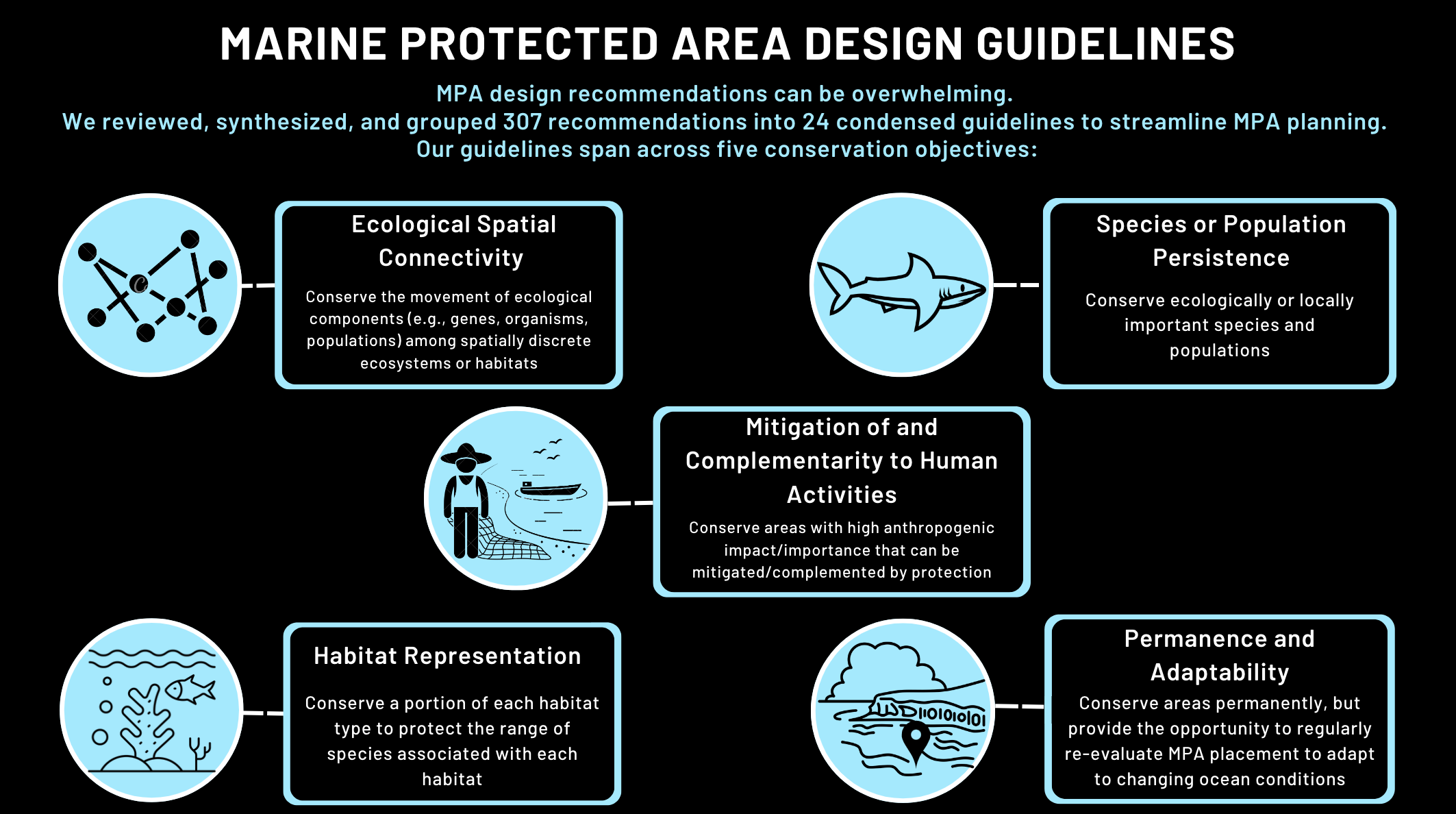

We then set out on our next adventure - consolidation… but not too much consolidation. We wanted to group these recommendations into condensed guidelines without losing the granularity that made the recommendations valuable. This meant many painful hours of grouping, followed by hours of reviewing groups, and even more hours of re-grouping and re-reviewing. We must have gone through 15 rounds of re-grouping before we were all on board with our final 24 condensed guidelines. We wanted our work to be useful to those who would use it the most - practitioners tasked with developing MPAs - so we turned to how to frame these guidelines. As part of the MPA planning process, our country partners often started with a list of conservation objectives, things like (1) preserving the connections between marine populations or communities, (2) ensuring the protection of at least part of each major habitat, (3) preserving vulnerable populations or age groups, (4) mitigating or complementing existing human activities, and (5) ensuring that the MPAs would be permanent but still offered protection despite a changing climate.

And so, our hundreds of recommendations were transformed into our final list of 24 MPA design guidelines, each one neatly sorted into one of the five conservation objectives.

Okay… but how can we use these guidelines?

All of our guidelines can be linked to specific conservation objectives, which will help practitioners narrow down the 24 guidelines that we present to a smaller list that can be implemented in their area. For example, if a key priority is to protect vulnerable and biologically significant habitats, two of our design guidelines can be considered:

- Protect diverse, biologically, and ecologically important areas, and

- Prioritize areas that will protect species that are ecologically, functionally, or commercially important, or vulnerable/endangered.

Alternatively, if a key priority is to minimize the negative impacts that an MPA will have on a fishery, three of our design guidelines can be considered:

- Create several, small MPAs to directly benefit fishers equally through juvenile and adult spillover,

- Balance socio-economic impacts of MPAs against biological benefits, attempting to select areas that minimize impacts to local fishers, and

- Place MPAs in areas that complement pre-existing managed areas, fishing grounds, and monitoring areas (e.g., placing MPAs in areas that are already protected by the local fishers, upstream of popular fishing sites, or adjoining existing nearshore MPAs).

We can go through the same process for other conservation objectives, like protecting areas of high productivity or protecting highly migratory species. In the end, we don’t expect practitioners to use all of the guidelines we suggest; we want them to be able to implement the ones tailored to their goals and community.

What about the data, models, and tools we mentioned?

What good are MPA guidelines if you don’t know what data, models, and tools to use to get started? In our paper, we highlight examples of datasets that can help with MPA design. For example, conducting social surveys can help pinpoint areas that are most important to locals for things like fishing or tourism. On the other hand, ecological surveys can help identify areas that are most likely to benefit from protection, like habitats that are important to several species for feeding, mating, or protection from predators. We also provide examples of models (e.g., prioritizr) that can be used to help identify the most efficient areas for protection by comparing many overlapping data layers, and tools that can be leveraged to make sure everyone, from fishers to government officials, can contribute to building their new MPA.

Why are we so excited about this work?

We had a unique opportunity to conduct a research project that was inspired by our partners around the world and turn the results into something that they could actually use in their day-to-day work. Many publications are focused on very specific projects, species, or areas, so it’s incredibly refreshing to be able to write a paper that can apply to a global audience. Even though this paper was developed with our partners in mind, we truly believe that this work will help all practitioners who are new to the MPA realm and will streamline future successful marine management efforts. At emLab, we strive for a “think-and-do” approach to all of our research, where we leverage data-driven insights to solve problems with our collaborators, and this work was exemplary of our approach.

Access our full paper here: https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.12946