As I write this emLab blog, World Trade Organization delegates from 164 countries have converged virtually on Geneva to propose an end to global fishery subsidies. How big are these subsidies? And what do we have to gain from their elimination? Surprisingly, while environmental NGOs, fishing industry advocates, and academics are replete with conjectures, they have not resolved these important questions, and so cannot offer concrete solutions to the delegates who must design subsidy-removal policies and sell them to WTO member countries.

Global fisheries land about 80 million MT of fish a year, which puts over $100 billion in revenue in fishermen's' pockets. Because well-managed fish stocks replenish themselves, this could be a highly valuable ecosystem service that pays enormous financial dividends. But in many parts of the world, poor fishery management institutions and subsidies that incentivize ever-increasing fishing pressure lead to overexploited fish stocks, so the cost of extracting this beneficial resource quickly eats through much of its benefit.

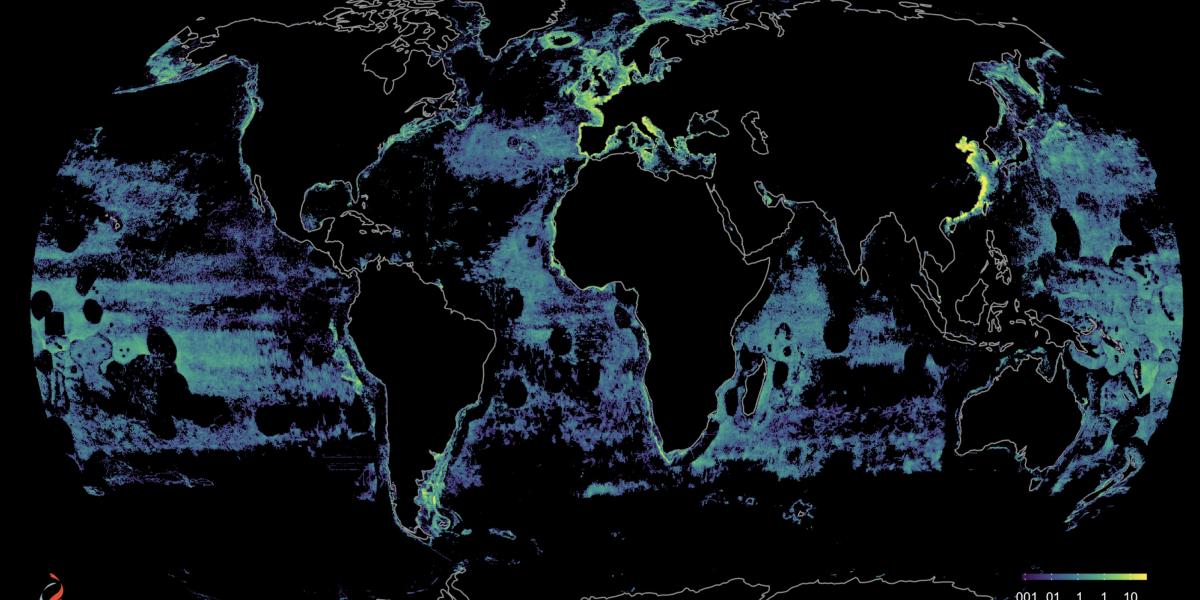

For example, a recent paper estimated that on the high seas (the 64% of ocean outside countries' EEZs) subsidies propped up a degree of fishing activity that would not have been economically rational without it. Using real-time vessel level tracks of 3,620 vessels (and calculating fuel usage and other costs), they found that costs and revenues were nearly identical. This corroborates the long-standing theory about the economic tragedy of open access resources, where stocks are depleted until all value of the resource is lost.

While some fishery subsidies are benign or even beneficial (for example, subsidies for surveillance or stock assessments), about $20 billion are allocated in ways that lower the cost of fishing, and therefore may be driving overfishing. The bulk of these are given as fuel subsidies. Because fuel makes up a large fraction of fishing cost, it is easy to see why paying $1.50 per gallon of fuel, rather than the market price of $3.00, may cause you to fish farther from port, stay out longer, and when aggregated up to the whole fishery, generally deplete fish stocks more.

So what would be the consequences of removing subsidies? I can offer three insights from the work emLab is doing to support the WTO delegates. First, the longer we delay, the harder it will be to dig out of the subsidy trap. Removing subsidies is an incredibly difficult task. Fishermen have relied on them for decades, and the further fish stocks are depleted, the more costly it will be to remove subsidies because stocks take time to rebuild. Second, countries are unlikely to act unilaterally. If Japan reduces its subsidies, other subsidizing countries who compete for the same stocks will gobble up much of the conservation benefit, leaving little for Japan to gain. In contrast, a coordinated effort could simultaneously benefit all countries. Finally, the potential upside is enormous. To see this, note that profit is given by p*F*B - c*F, where p is price, F is fishing mortality, B is biomass of fish and c is the (subsidy-inclusive) cost per unit effort. In open access, profit is zero, so B=c/p. This implies that the elasticity of global fish biomass with respect to the subsidy is exactly 1.

Our preliminary data suggest that subsidies comprise about 35% of costs, so applying this elasticity, it is within the realm of possibility that global fish biomass could increase by 35%. This will be more pronounced in poorly-managed regions, and less pronounced in well-managed regions. Such a comprehensive and coordinated move could confer an enormous benefit to the world's fisheries, though it will take time to materialize, and will have costs to fishermen as we transition to the new equilibrium.

The WTO delegates are currently negotiating over nine distinct proposals for what subsidy-removal could look like on a global scale, each affecting different countries, targeting different behavior, and having vastly different equity and conservation outcomes. With support from the Pew Charitable Trusts, an emLab research team is developing models and empirical methods to evaluate these proposals and inform the design of this globally-relevant policy intervention.