While the efficacy of climate policy is one of the top concerns of law makers, an underlying concern is who bears the cost of these policies. For instance, last November Washington state proposed a new pollution fee for the use of fossil fuels and electricity generation (Initiative 1631). This was the second carbon tax initiative proposed in the State (the first was Initiative 732), both of which failed. Why did state residents vote against a policy that could reduce Washington’s carbon emissions? It was largely opposed due to environmental justice concerns.

First, I’ll start with the basics: what is environmental justice? As this recent paper explains, environmental justice is achieved when no group experiences a disproportionate share of a policy’s negative environmental consequences. Environmental justice concerns are not new, but in the case of climate policy, they have gained higher public discussion as policy makers have tried to pass legislation to reduce the increasing trends of global carbon emissions.

If we would all benefit from reducing carbon emissions, why would people be opposed to environmental regulation?

Leaving aside interests from private parties, some groups have expressed concerns about the implications of environmental policy in terms of environmental justice. To put it simply: imagine that an entire city would benefit from opening a recycling facility and the only available lot is next to a historically low-income community. The city government knows that this recycling facility will benefit the entire city, so it starts construction. However, pollution near the facility and low-income community will increase. When factoring in health effects, will these families in fact be better off with the new facility?

As environmental regulation becomes more complex, analyzing the environmental justice consequences of a policy gets even more complicated. Let’s take an example familiar to California residents: the cap and trade program (C&T). The California state government sets a cap on the amount of carbon emissions and allows regulated facilities to trade emission permits with each other. This policy would reduce carbon emissions, which has global benefits. However, it does not directly target local pollutants that could have local costs in terms of health. With respect to environmental justice, we should pay attention to the changes in air quality associated with the policy implementation.

What are the environmental justice concerns in the C&T example?

One concern is whether disadvantaged communities are systematically located downwind from polluting facilities that together with atmospheric conditions cause them to experience a higher exposure to local pollution. This concern is known as inequality in pollution exposure. Another concern is whether firms located near disadvantaged communities are producing higher emissions due to buying more permits under the C&T program. This concern is referred to as the incidence of environmental policy.

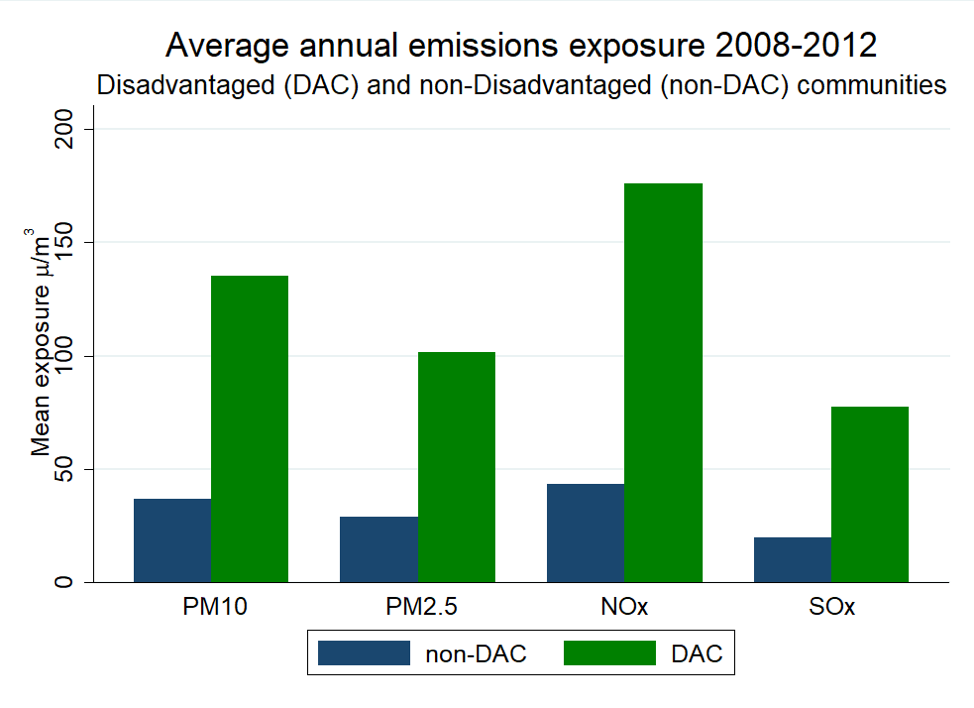

Consider Figure 1 which shows the average pollution exposure before California’s C&T began. Disadvantaged communities (communities with low income households and high minority population shares) experienced higher levels of pollution. This suggests that from 2008-2012, there was inequality in pollution exposure across California’s communities. Given this, it is not surprising that California incorporated Environmental Justice advisories to hear the voices of the people who are exposed to the highest levels of pollution and provide advice on the implementation of AB32.

Figure 1. Average annual emissions exposure. Author calculations using data from CARB.

emLab’s Climate & Energy program is currently exploring whether California’s Assembly Bill 32 (AB32) has helped disadvantaged communities experience lower levels of air pollution. AB32 is California’s state-wide climate policy that mandates reductions of greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. Kyle Meng and I considered the emissions of facilities regulated under C&T, their location, and meteorological conditions to calculate the pollution exposure faced by California communities after C&T was implemented. Thus, trying to analyze the policy incidence of environmental markets on disadvantaged communities.

How can environmental policy be designed such that it does not disproportionately hurt the most vulnerable communities?

Environmental justice concerns are not unique to C&T but to environmental markets and environmental policies in general. One recent attempt to start tackling these challenges was when Senator Kamala Harris and U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposed the Climate Equity Act which aims to give vulnerable communities across the U.S. a seat at the table during discussions over environmental legislation. Designing policies that aim to improve environmental outcomes while considering the communities that bear the cost of these policies and their historical environmental exposure could help prevent future environmental justice concerns.

Environmental policy has the power to improve our quality of life. This, however, should not come at the cost of hurting already vulnerable communities. As market instruments become a tool for tackling the climate crisis, considering how these markets will affect vulnerable groups is essential in order to have not only sustainable but also equitable growth.