Maybe this situation sounds familiar: you are out to dinner at a nice restaurant with a group of friends. As you sit down, someone suggests splitting the bill evenly. As a result, you suspect that some of your dear friends order more lavishly than they would have if everyone paid for their own food and drink (not you, of course!).

This free-riding dynamic can show up in the home too. Your son always leaves the lights on when he goes out, your daughter cranks up the thermostat in her room as soon as it gets below 70 degrees outside, and your spouse takes looooong showers every day. Yet when the water or energy bill comes, each member of the household doesn't have to pay for his or her share. You may suspect this leads to more wasteful behavior than if your spouse had to pay per minute in the shower or your daughter's allowance were docked based on the energy used to heat her room. My coauthors, Seema Jayanchandran (Northwestern) and Sarojini Rao (Chicago), and I shared your suspicions. We describe our investigation of free-riding within the home in the context of water consumption in a recent working paper. I'll summarize a few of the key insights and how they relate to environmental policy.

What is different about the situation with your friends at dinner and your family's utility bills? A lot of things, but two are particularly relevant.

First, both your choice of what to order for dinner and your energy or water use decisions impose externalities on other members of the group - your friends or your family, respectively. But the latter also creates externalities beyond the group through the environmental consequences of energy and water consumption. (Of course, if your friends order Brazilian beef raised on recently deforested Amazonian land or almonds from drought-stricken California, then their consumption also creates environmental costs beyond the group.)

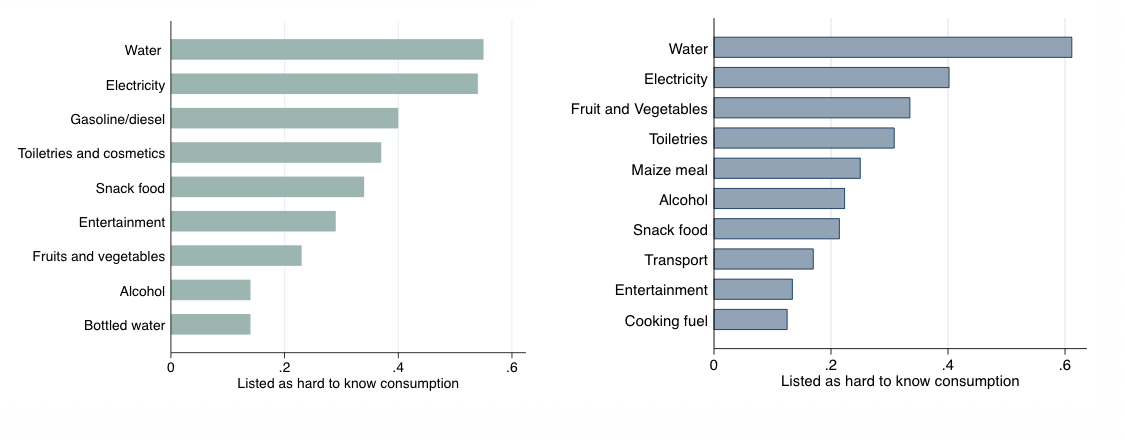

Second, the problem among your friends is considerably easier to solve than the one you face with your family, and not just because friends are easier to deal with than family. At the end of your meal, you and your friends could get a bill that itemizes how each individual contributed to the total. Or you could decide upfront that everyone pays for what they order. This isn't so easy to do with your water or electric bill. Most households get monthly bills that reflect aggregate consumption, making it difficult to divvy up responsibilities after the fact. Individuals in both the U.S. (green) and Zambia (blue) report that it is particularly difficult to keep track of their spouses' water and energy use. While you may not think that your spouse's long showers matter that much for overall water use, consider that nearly every household in U.S. faces a water bill that reflects their aggregate - rather than individual - usage. And some face even more distorted incentives if their landlord pays the bills or if they share a meter with other apartments in their building.

Response to survey question "Which categories of your spouse's consumption are most difficult to know? (pick two)".

What does all of this imply for environmental policy? It means that the tax needed to address the environmental externality from consumption will have to be even higher to also address the externality within the home. This is not necessarily a problem if all households are equally prone to this kind of free riding behavior. However, if some households have found ways of better policing each other's consumption - or ways to cooperate - then the cooperative households will be over-taxed while less cooperative households will be under-taxed.

As long as it remains more difficult to split up the utility bill than the dinner bill, this problem is likely to persist. Other interventions, including technologies such as smart meters or prepaid electricity meters, that make it easier to keep track of individual usage may help. Or, with the holidays coming, try a little altruism, and feel the cost your water and energy use impose not just on the planet but also on members of your own household.