Water sustains life worldwide and is an essential input into all economic activity, with no close substitute. However, climate change, land transformation, overconsumption, and other human activities are pushing the hydrological cycle out of balance, exacerbating water scarcity, food insecurity, and social vulnerability across the globe. While water has traditionally been studied locally, new forms of satellite-based data and recent innovations in hydrologic modeling allow us to study these dynamics at global scale. A first-of-its-kind report from the Global Commission on the Economics of Water, co-authored by emLab's Director of Climate & Energy, Tamma Carleton, data scientist Maren Ludwig, and Bren PhD student Sandy Sum, leverages these new data sources to assess the critical risks associated with freshwater imbalances globally.

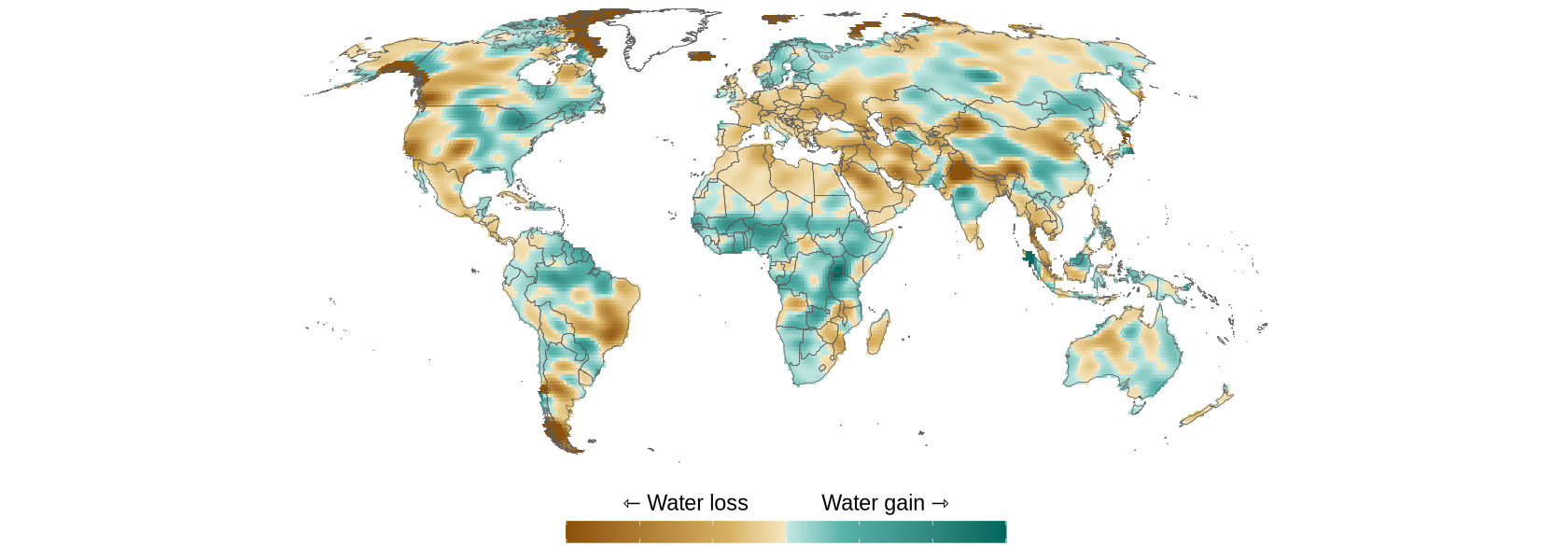

Figure 1. Satellite-based estimates of changes in total water storage between 2003 and 2022.

Using satellite-based estimates of changes in the total volume of water stored above and below the surface for all locations on Earth (called “total water storage”; Figure 1), combined with climatological, agronomic, and demographic information, the emLab team assessed the social and economic vulnerabilities posed by freshwater imbalances and the extent to which climate change and irrigated agriculture are driving these imbalances. The analysis shows that few people reside, and few cropped acres exist, in locations that are neither rapidly losing nor rapidly gaining water. Notably, about 2.9 billion people and half of global food production are located in regions experiencing rapid water loss.

Their findings reveal that global warming and irrigation practices have intensified water loss over the past two decades, with agricultural water use outpacing the drying effect of warming in regions where irrigation is prevalent, like northwestern India and the Ogallala aquifer of the United States. If current trends continue, rapid declines in water storage could make irrigation infeasible in which case 23% of global cereal production would be at risk, posing a serious threat to food security worldwide.

The report highlights that while water is usually managed locally, local management decisions have increasingly global consequences. Specifically, the authors quantify a network of atmospheric water exchanges in which land use changes in one area, such as deforestation, shape rainfall elsewhere by disrupting evapotranspiration processes.

Utilizing global modeling of atmospheric moisture transport, high-resolution data on socioeconomic variables, and estimates from the literature linking total economic output to changes in precipitation, the researchers estimate, for the first time, the economic significance of this interconnected network. The analysis shows that substantial amounts of rainfall, especially in lower-income areas, originate from terrestrial sources that could be disrupted. If rainfall originating from deforestation hotspots were to disappear due to land conversion, for example, the authors estimate that economic growth rates in Africa and South America could drop significantly – by 0.5 and 0.7 percentage points, respectively. This suggests that atmospheric moisture flows originating from land are of great socio-economic importance, particularly in regions of low development that are heavily dependent on agriculture.

Ultimately, the findings point toward a future of potential water risks with substantial ramifications for food security and economic stability. The report emphasizes the importance of viewing the hydrological cycle as a global common good and outlines ways we can collectively design economic incentives to stabilize our water resources.