In a paper on human-wildlife conflict published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a team of UCSB students utilized geospatial data and novel data science methodologies to outline the potential impact of climate change, agricultural changes, and population shifts on conflict risk for Asian and African elephants. Read how the team went one step further to involve stakeholders and collaborators on the ground to make sure their findings were relevant to the people and places behind the data.

When you look through a pair of binoculars, distant scenes swell in size, as if you stand mere steps away. The viewfinder acts as a portal to a realm once concealed to the naked eye, establishing a link with the unseen and immersing the observer into a landscape distant from their own.

Similarly, in the realm of data and geospatial analysis, researchers find themselves transported across vast distances, bringing far-off places and subjects into focus. Through virtual "field work" accessible from their computers, scientists can travel to the depths of Amazonian forests or climb aboard fishing vessels in the open sea with seemingly just a few clicks. Using collections of complex datasets, they can collect and analyze information like changes in land use, atmospheric conditions, and species populations, all from a distance. Advanced data tools and methodologies like remote sensing and geospatial modeling have made it possible for us to dive deeper into environmental questions anywhere in the world.

At UCSB’s Environmental Markets Lab (emLab), a team of researchers is working to understand current and future threats facing the world’s largest land animal - elephants. Spanning Africa and Asia, elephants serve as vital keystone species, providing essential ecosystem services crucial for the survival of other species in their habitats. However, habitat loss, poaching, and human-wildlife conflict have led to a drastic decline in elephant populations. African elephant numbers have plummeted by 98% since 1500. Similarly, Asian elephant populations have been cut in half within a mere century. Elephants are one of many species facing extinction. With nearly 40% of all species at risk of extinction by the end of this century, the very web of life that we depend on seems to hang delicately by a thread.

Like many global challenges, the factors contributing to the current biodiversity crisis are deeply intertwined. Climate change, shifts in agricultural footprint, and human–wildlife conflict all play an important role. However, addressing just one aspect overlooks the complexity of the problem, not to mention misses the point of meaningful work, which is done in collaboration, stretching across time, place, and discipline.

In 2021, UCSB and Conservation International (CI) launched a series of research projects through generous support from John Arnhold to drive collaboration between environmental scientists and stewards. One such research initiative aimed to support CI’s goals through SPARCLE (Spatial Planning for Climate Change: Land Use for Conservation, Agriculture, and Energy). SPARCLE operates at the intersection of applied science, big data, and geospatial modeling. With over 20 institutions involved from around the world, SPARCLE examines how species may respond to climate change alongside anticipated shifts in human population and land use.

One project wanted to understand how human-elephant conflict risk may change as human populations expand and climate change impacts intensify. As agricultural and developmental activities continue to encroach upon elephant habitats, these massive animals, weighing up to 7 tons, are compelled to search for food in areas inhabited by humans. This often results in catastrophic damage to homes and farmlands, threatening the livelihoods of entire communities and jeopardizing the lives of both humans and elephants. The project team wanted to investigate whether climate change could exacerbate future human-elephant conflict.

Arnhold Fellows Roshni Katrak-Adefowora and Taylor Lockmann kicked off the project with support from Patrick Roehrdanz at CI and Bren Assistant Professor and emLab affiliate, Dr. Ashley Larsen. The first few months were spent learning how climate change variables and land use projections may be used to predict human-elephant conflict patterns across the African savanna elephant range. Grace Kumaishi joined the project a few months later and worked to expand the project scope to Asian elephant conflict mapping. By the time Mia Guarnieri joined the Arnhold Fellow cohort in the second year of the project, the team was ready to dive deeper. Grace highlighted that "because of the iterative research done by Roshni, Taylor, and others from the beginning of the project, we had promising methodology to use in our analyses once Mia joined the team.”

While the team felt confident in their methodology and the suite of global geospatial and socio-economic datasets available to map conflict risk under various climate and development scenarios, Mia expressed their uncertainty about the practical utility of their models in real-world settings. "How can we be certain that this big, abstract data can truly support on-the-ground conservation efforts?" she questioned. To ease this uncertainty, Mia and Grace knew it was important to garner feedback and input from the experts and communities in both Africa and Asia.

So with the help of CI collaborator Dr. Ezequiel Fabaino at the University of Namibia and Dr. Mayukh Chatterjee based at the Chester Zoo in Asia, they incorporated what Mia describes as a "sanity check" into their methodology. In other words, after modeling a region, the UCSB-CI team would share their initial findings and maps with partners on the ground to see if their data-driven insights aligned empirically with reporting from local communities. Grace emphasized the crucial role played by experts from these regions, stating, "Without the input from our regional collaborators, we would have felt much less confident in our findings."

Models are essential for conceptualizing interacting processes and for envisioning alternative scenarios. However, Grace and the team understand there are limitations with really large, global models. To manage areas influenced by social and ecological processes operating regionally or globally, it is essential to ground issues in the places where stakeholders live and work, making abstract connections explicit in a real landscape. As a result, local knowledge and expertise was an integral part of the model development.

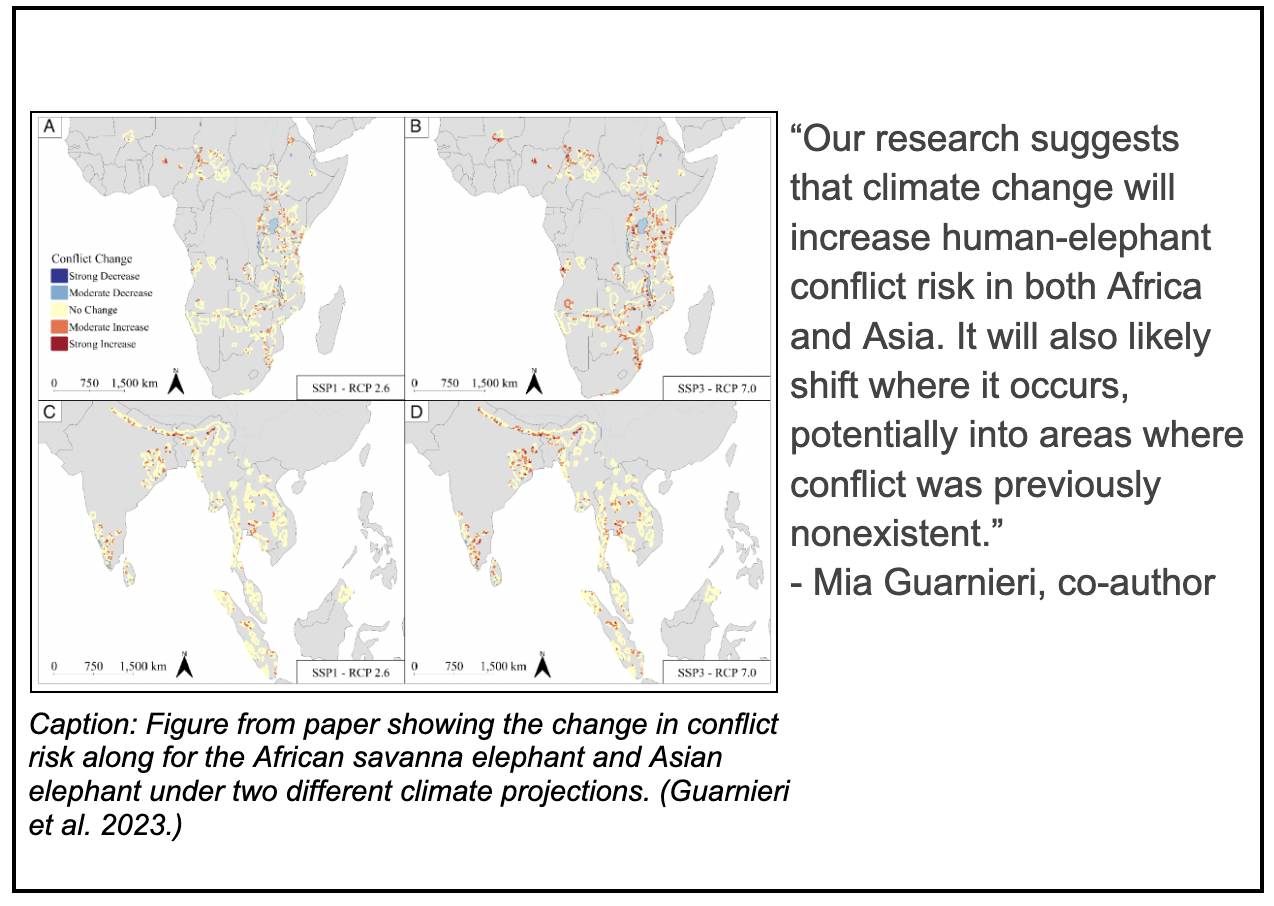

Mia and Grace are excited to see stakeholders use the geospatial models they developed to examine and visualize human-elephant conflict across time and space. According to Mia, their research suggests that climate change is likely to increase the risk of human-elephant conflict in both Africa and Asia. Moreover, it may also lead to a shift in where conflict occurs, potentially into areas where conflict was previously nonexistent. Discoveries like these shed light on the possible trade-offs associated with various management approaches and the degree to which stakeholders can influence decision-making and outcomes. “The goal of our project was to help conservation managers more effectively plan and implement conflict mitigation strategies,” Mia stressed. “We wanted to make sure that we could apply our findings.”

Ultimately, solutions will rely on the sustained involvement of local stakeholders in partnership with researchers, scientists, and decision-makers to identify management actions that have the potential for lasting positive change. Meanwhile, Mia and Grace have transitioned leadership to the next cohort of Arnhold Fellows, who are now working on integrating and downscaling these research findings into real-world management strategies, particularly in the Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area - home to the largest remaining population of African elephants.

To read the full paper, click here.